Two weeks ago, I confirmed something I first started to suspect years ago: that my routine chest pains, nausea, and general sense of being stabbed through my abdomen after every meal are not simply me exaggerating. Turns out, these are the symptoms of an immune disease called eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) that I’d had undiagnosed until now.

Googling my new diagnosis, I discovered something unusual—EoE is more common in men, by a ratio of about 3:1. This was surprising to me considering that, because the female immune system is stronger on average, women are significantly more prone to everything from autoimmune diseases to food allergies to asthma. Like these, EoE stems from an overactive immune system, and I couldn’t decipher what would make this condition different.

While some researchers propose genetic or hormonal factors, these theories remain unproven. Ruminating on the twenty-two years I spent oblivious to the source of my persistent pain, I couldn’t stop wondering: are there really more men with EoE, or are there just more getting diagnosed?

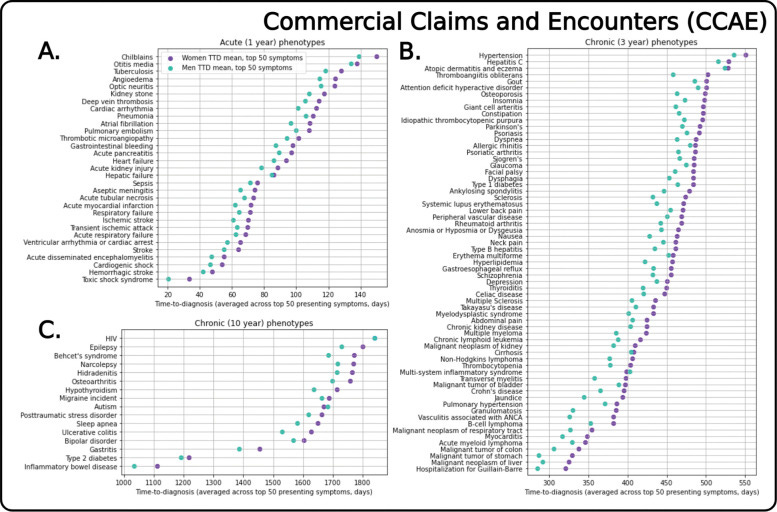

It’s no secret that women face greater diagnostic delays than men do. In the ER, we wait about 11 minutes longer to be seen for heart attacks and 16 minutes longer to receive medication for acute abdominal pain—a gap that widens even further when it comes to chronic conditions. One study looking at 112 diseases found that women took longer to be diagnosed with 108 of them, by an average of 134 days for long-term illnesses.

Here’s a graph showing the average time-to-diagnosis for each condition in the study:

Often, women’s symptoms aren’t diagnosed because doctors mistakenly view them as psychological. Heart attacks may be seen as expressions of panic, autoimmune diseases taken for depression, epilepsy dismissed as conversion disorder (which is essentially a modern term for hysteria, the diagnosis once used to dismiss all kinds of physiological and psychological symptoms in women).

Like those patients, women today end up relying solely on psychiatric treatments that, at best, can only camouflage their suffering, leaving them unprotected against the dangers of their undiagnosed conditions. One 1965 study at London’s National Hospital even found that, among 85 patients diagnosed with hysteria a decade earlier, a full 60 percent had organic diseases like epilepsy or migraine—and that half of the sample had either died or become disabled in the meantime.

I was given multiple psychiatric diagnoses before any doctor ever thought to perform the endoscopy that detected signs of my EoE. Along with this were other diagnoses that were only implied, by doctors who refused to consider that my failure to gain weight stemmed from anything except my own psychology.

When I told them eating physically hurt, doctors took this as evidence of an undiagnosed eating disorder—or, at the very least, an anxiety about the act of consumption. “Don’t worry about eating too much,” one told me at seventeen. This felt less like permission and more like a command, an accusation about my ability to take care of myself.

Eventually, I stopped mentioning my food-related symptoms to doctors. I became convinced that I was just afraid to eat and invented my own string of psychological reasons for this aversion. I was a picky eater, sensitive to the touch of food to my mouth. I was overly fastidious, taking four bites to finish a potato chip because I so deeply craved precision. I blamed my ADHD for my inability to maintain focus on the motions of my fork. Wondered if I might have restrictive ARFID, a disorder that can cause “lack of interest” in eating. Apologized my way through meals, always guilty for holding people up.

I only decided to take one final stab at medically addressing my symptoms after a series of chance conversations revealed to me that many people in my life rarely ever feel stomach pain: something I had always assumed impossible.

Still, as I boarded the train to my new gastroenterologist’s office, I was filled with preemptive shame for wasting her time with my amorphous, meaningless pain. I told myself this was my opportunity to prove to myself, once and for all, that nothing was wrong with me. To put this possibility to rest. When the doctor entered the exam room, I cringed as I told her my symptoms, waited for a punitive comment about my weight, or else some prescription placebo.

But she reacted without the calm dispassion I was used to receiving from doctors. Instead, she rattled off a list of tests and said that it was important not to wait on them. Her determination made me woozy—leaving her office, I had this unexpected sense that, possibly, what was wrong with me lay somewhere outside of my hands.

The phrase “man flu,” while lacking a scientific basis, is sometimes used to describe the more severe colds and flus men experience, which include longer recoveries and more frequent hospitalizations. Coming across this term, it strikes me that more severe displays of illness are viewed as genuinely greater suffering in men when women showing serious symptoms are more likely to be assumed dramatic or mentally ill.

This discrepancy isn’t just anecdotal. For example, one 2021 study found that, when shown images of people visibly expressing pain, people overestimated the pain of male faces and underestimated the pain of female faces—and they were also more likely to judge female patients as likely to benefit from psychotherapy.

Like many women, I was afraid of seeming melodramatic, and I made it my goal not to tell anyone how even slim pieces of romaine sometimes felt like blades to my gut when I swallowed them. At the doctor, many of us face an impossible dilemma: showing our pain may get them dismissed as over-emotional, but suppressing it makes it seem like nothing’s wrong.

I can’t entirely blame doctors for making false assumptions when they barely get any time with us—when they don’t know more than a snapshot of our experience, comparing patients to textbook examples can be all they have to go on.

In this way, the problem doesn’t lie in doctors alone but in the stereotypes used to make quick judgments. Stereotypes are what say a skinny teenage girl who’s scared to eat must always be anorexic rather than having EoE—even though less than 6 percent of people with eating disorders are medically underweight.

And after looking through research on EoE, I worry that stereotypical ideas of the disease may actually be working against women who have it. One study, for example, found that men with EoE were more likely to have symptoms seen as central to the condition, such as trouble swallowing, while women more often present with secondary symptoms, like the abdominal pain and nausea I have.

Worse, which of these symptoms are seen as relevant isn’t just decided by societal beliefs (there are very few societal beliefs about a disease as obscure as EoE) but actual clinical definitions based on research. Because women have historically been excluded from clinical trials—in the US, for example, clinical trials weren’t required to include female participants until 1993—much of our medical knowledge is based around the male experience. This leaves doctors erroneously dismissing women whose heart attacks involve jaw pain and fatigue instead of the stereotypical chest pain.

Could EoE the same phenomenon exist for EoE—one where female symptoms, left outside the original definition, continuously fail to catch doctors’ attention?

My next few weeks after that gastroenterologist appointment were consumed by testing, which I feared was purposeful until one morning when I listened, still blurry with anesthesia from my endoscopy, as the doctor told me she’d discovered visible aberrations in my body.

Still, confirming a diagnosis required a biopsy, which meant waiting another couple weeks. I tried to avoid Googling the suspected diagnoses in the meantime, trying not to get attached to the idea that I’d spent my whole life misdefining my body—that daily life wasn’t supposed to be this painful.

But then, two weeks later, I opened the Zoom link for my follow-up appointment and heard my gastroenterologist say something I’d never heard from a doctor’s mouth: “It’s a good thing we took a look at this.” Rather than wasting resources on a healthy but paranoid woman, the biopsy showed unquestionable proof of EoE.

In that moment, it was like I became new to myself. I was no longer a slow eater, failing at the most basic task. No longer lazy, deficient, incapable of being a real adult. For once, I wasn’t just some fragile girl complaining over nothing, unable to properly assess her body’s sensations. Instead, my white blood cells were out of line, filling my esophagus with errant clusters, leaving me in pain I could not control.

A clear theme emerges when you look at the breakdown of diseases by gender. Men are more prone to cancer, Parkinson’s, coronary heart disease: illnesses we all know to take seriously. Women, meanwhile, receive far more diagnoses of anxiety, depression, and medically unexplained conditions like chronic Lyme, POTS, IBS, and Long Covid, which lack identifiable cause. In fact, most medically unexplained conditions are at least twice as common in women—for some, nearly 90% of patients are female.

Unfortunately, many of these conditions are probably medically unexplained because they’re more common in women, who are less represented in clinical research. But instead of prompting new studies, the high prevalence of medically unexplained conditions in women is more often used to dismiss their symptoms as products of their imaginations—making it harder for these conditions to be taken seriously and actually reducing the research funding they receive.

Patients with medically unexplained conditions then struggle to cope with having no clear treatment path or means of understanding their symptoms. They may also face discrimination from doctors, who tend to respond more negatively to patients whose symptoms are harder to explain. Fearing the threat this uncertainty poses to their professional competence, doctors may frame these patients as fakers and even refer to them by various disparaging nicknames: thick folder patients, frequent flyers, victims of familiar face syndrome.

Learning about medical sexism cemented my belief that any test the doctors ran on me would inevitably come back clean. But despite knowing that a negative test doesn’t mean perfect health, I still used this logic to convince myself that my symptoms were my own fault—and like so many other women, I believed what doctors said until I no longer trusted my body when it said it was in pain.

It still startles me that, after all this time, all someone had to do was look inside my body to see answers glaring back. Unfortunately, my experience is anything but rare. Recently, for example, I interviewed Kylie Fiore, who has gastroparesis, a condition leading to partial paralysis of the stomach. Kylie’s symptoms sound harder to disregard than mine ever were—because her stomach muscles move more slowly, she often struggles to eat without vomiting—yet Kylie’s account of her interactions with doctors is chillingly familiar.

“When you're a teenage girl, and you're throwing up all the time, and you're losing a bunch of weight, doctors aren't going to immediately assume that there's something wrong with you,” Kylie explains. But why is this true? How much do women have to suffer before our symptoms are worthy of alarm?

Like me, Kylie was either dismissed entirely or told she had an eating disorder by many of her doctors—sometimes even after her official diagnosis. I can’t stop thinking about what could’ve been different for me, or Kylie, or any of the millions of other women whose doctors have nothing to offer but scrutiny, if we were believed from the first time we said something felt off.

For the past two weeks, I’ve felt myself spiraling out, disoriented by the knowledge that eating is not the arduous task I know it to be. I find myself picking at plates of rice and wondering what consuming it would feel like from another body—like absence? An oblivious relief?

I wish I’d been diagnosed before the idea that food means pain was ingrained in me. I can’t stop obsessing over this possibility. Could I have lost less of myself to the relentless return of my symptoms? Could I have avoided the years I spent redefining my hurt as a weakness?

Thank you for sharing this, this was fascinating for me to read as a man who had a very young age was diagnosed with the same condition. What’s even more interesting, Is that in retrospect, opposite to you, I am saddened and felt wondering what it would’ve been like to have had the psychological relational elements of my health taken seriously, and instead only the physical visible health issues mattered. I only ever had food, allergies, and chest pain… recognizing this asymmetry in your story, makes me feel a sense of connection, thanks.