I don’t recognize the breathtaking freedom of painlessness until pain returns: a circle of stabbing suddenly holding my ribcage hostage, pinning me against the chair. Only when this happens do I wish I’d noticed the freedom of gliding down the sidewalk without having to tighten my muscles against the pain, the effortlessness of nodding my head to a HAIM song while I brush my teeth.

In Life Sciences, Joy Sorman writes that “...it’s crazy how easy things are when you’re in good health, as though existence is an abstract, an idea almost, just a word, and how it becomes terribly concrete when you’re in pain…” Still, returned to my neutral state, where pain no longer dominates me, I keep trying to understand this other version of myself. I flip through my journals, listen to voice recordings I’ve made, but quickly I realize none of these are complete—none of these contain what pressed against me from the inside, or the intensity of its total hold on me. Even within the same body, my former pain is elusive, impossible to reconstruct.

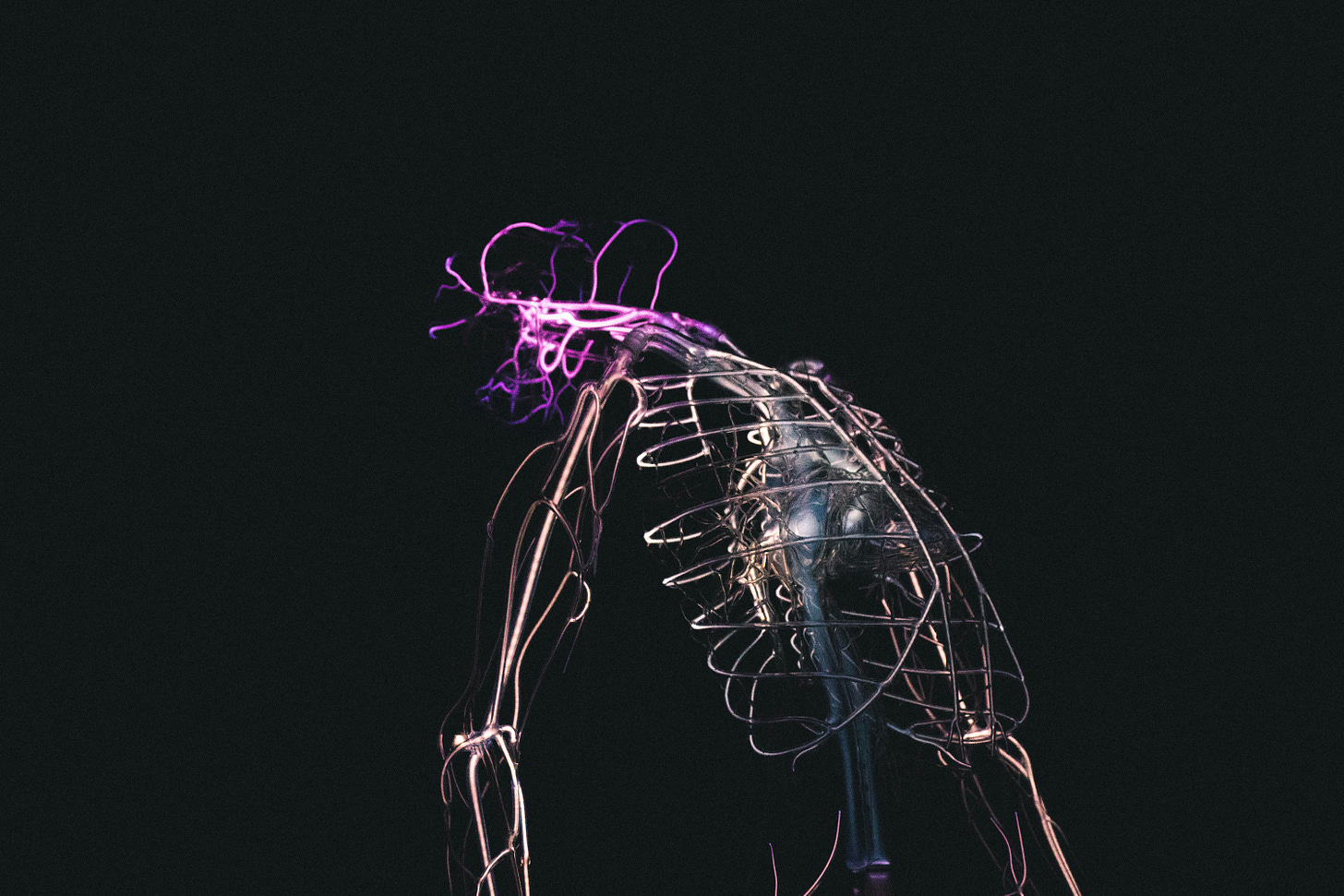

Even more impossible are our attempts to understand the pain of other people. In The Body in Pain, Elaine Scarry writes:

“When one hears about another person's physical pain, the events happening within the interior of that person's body may seem to have the remote character of some deep subterranean fact, belonging to an invisible geography that, however portentous, has no reality because it has not yet manifested itself on the visible surface of the earth.”

Trying to describe my symptoms, I fall back on phrases too vague to carry real meaning. I say, Pain, pain, unable to specify further. I can barely locate the sensation inside me: it seems so total, so of itself. I call it stomach pain even though my lab results say differently, because this is an easy explanation for being unable to eat. I compare it to period pain, omitting that, unlike a menstrual cramp, my current pain has no obvious cause and no certain endpoint. My only referent is my personal history of hurting, which I can never align with anyone else’s.

Being in pain, Scarry argues, is the ultimate form of certainty—because we’re consumed by it, we know, without the slightest doubt, what we feel. Meanwhile, hearing about another person’s pain is the ultimate form of having doubt. “Whatever pain achieves,” writes Scarry, “it achieves in part through its unsharability… Physical pain does not simply resist language but actively destroys it.”

The field of medicine only makes it harder to understand other people’s pain. Because of its need to standardize and quantify, medicine strips illness of its texture, narrowing it into neat categories that can only pretend to capture the total experiences within them. When it comes to illnesses we don’t live with, then, we tend to falsely perceive them as detached: compartmentalized into discrete symptom clusters that are then addressed with medications or therapies, discussed briefly in appointments and otherwise put out of mind. Food allergies and Celiac disease simply mean avoiding certain items on the menu. Endometriosis is a predictable anguish, distilled into brief monthly interruptions that leave no lasting mark. And a whole host of other conditions appear as no more than an obligation to swallow a few pills every day—especially when a patient is young, and looks healthy, and doesn’t let their pain show through.

But the reality is that illness is stapled to the body, and you can never escape from your body. In Sorman’s Life Sciences, the protagonist, Ninon, finds that her arms, where her excruciating chronic pain is concentrated, become her body’s “center of gravity.” Even when symptoms are easier to tune out, they manifest as irritability, a short attention span, a desire to avoid standing for too long, or else a clinging fear that you will never have a handle on yourself.

For example, even with food that’s never caused me any kind of pain, I find I can never eat without a twinge of anxiety. When it tastes good, this feels more like deception than pleasure, and so I choose my meals based on what I can expect to feel in the days that follow. I’m unfazed by pairings that make other people recoil: I dip French fries in water, mix dill pickle chips into oat milk just because I can.

Meanwhile, my familiarity with pain makes me unsure of how to respond to it. Pain is an alarm signal, teaching us what to avoid, which means that eating requires doing something I’ve been endlessly conditioned not to. To eat I have to mentally detach, ignore the needling anxiety that says I’m putting myself in danger. Now I burn my hand on the stove by mistake and barely flinch. I wear new shoes and remove them at the end of the day to find my ankles caked in blood from a wound I couldn’t sense.

Not to mention that illness is more than just symptoms. In February, I spent hours calling every radiology center in a ninety-minute radius, just to be told that they needed me to personally fax them or have my doctor alter the lab order based on their hyper-specific requirements or wait until June—just to cancel the appointment I finally got when they told 48 hours ahead of time that there’d be a massive copay. Other times, I lose time calling CVS to ask why they won’t refill my medication, or even walking over there in person because the robo-voice won’t connect me to a human. Then there’s the frustration of planning out meals in excruciating detail and bringing food every time I leave the house, of fasting from water before tests and listening to the seventy-year-old technologist ramble on about his sex life and his unnerving political opinions, of feeling like I’m going to collapse inside when I spend all day trying to work despite the jabs of pain in my chest and then see other people simply cook, eat, and forget about it. Am I misunderstanding something? I ask sometimes. Does anyone really go without pain? I Google this question over and over, but every time, the results just say I should talk to my doctor.

The worst of this is that I know I’m luckier than a lot of people: because I have health insurance, because I can take time to go to an appointment on a weekday, because I don’t have health issues severe enough to prevent me from working or having a social life.

Of course, illness’s impact isn’t always negative. Interviewing people about their health, I always ask at the end about whether there’s anything important that I haven’t asked about, and I’ve noticed that people often launch into a description of everything they’ve gained from their condition—how being unable to eat from a stomach condition makes them more attuned to their friends during meals, or how much they value the connections they’ve formed with others who share their chronic pain disorder.

When I interviewed Cindy Kaplan, author of the Substack Chocolate-Covered Lox, about her experiences dealing with airborne food allergies at work, she suggested that employers shouldn’t see allergies as a drawback for potential employees. After all, Kaplan said, her food allergies have required her to develop skills that are incredibly valuable in the workplace. “You have to be really good at thinking about minutiae,” she explains. “You keep a lot of information in your brain at all times. You have to be a strong advocate for yourself, which often can play out really helpfully in the workplace [since] you don't shy away from a task.”

Unfortunately, employers who don’t have food allergies themselves are rarely aware that this condition affects more than just diet—and conversations like this one made me curious about what else we miss when we limit our understanding of a health issue or disability to just its biomedical symptoms. To investigate further, I spoke with a number of patients whose conditions range from epilepsy to dermatillomania about how their conditions color their personalities, worldviews, and everyday lives. I’ll be sharing what I learned in my next set of posts, a series of profiles each spotlighting a different person’s experience.

If you’re interested in sharing your experience with an illness or disability, feel free contact me at zoecunniffe@gmail.com or through Substack direct messages.