Over the past couple months, I’ve become a regular at an establishment I cannot explain. Officially, its name is Harborside Financial Center, but without any real idea of what this means, I end up referring to it in a number of ways when someone asks where I’ve been: the financial mall, my fake office, the abandoned mall, or, most often, just Harborside.

At Harborside, I sit at various tables in a huge atrium area with looming glass windows where you can stare across the river at the unassuming gleam of Manhattan.

Around me there are an assortment of fake plants and bookshelves sporting everything from an encyclopedia of New Jersey to Pharrell Williams’ Places and Spaces I’ve Been.

It feels like a hotel lobby, except that there’s no hotel room waiting for me upstairs. Instead, there’s just a scattering of office workers taking advantage of the free wifi or eating lunches from the food court off to the side that hardly anyone ever seems to go in.

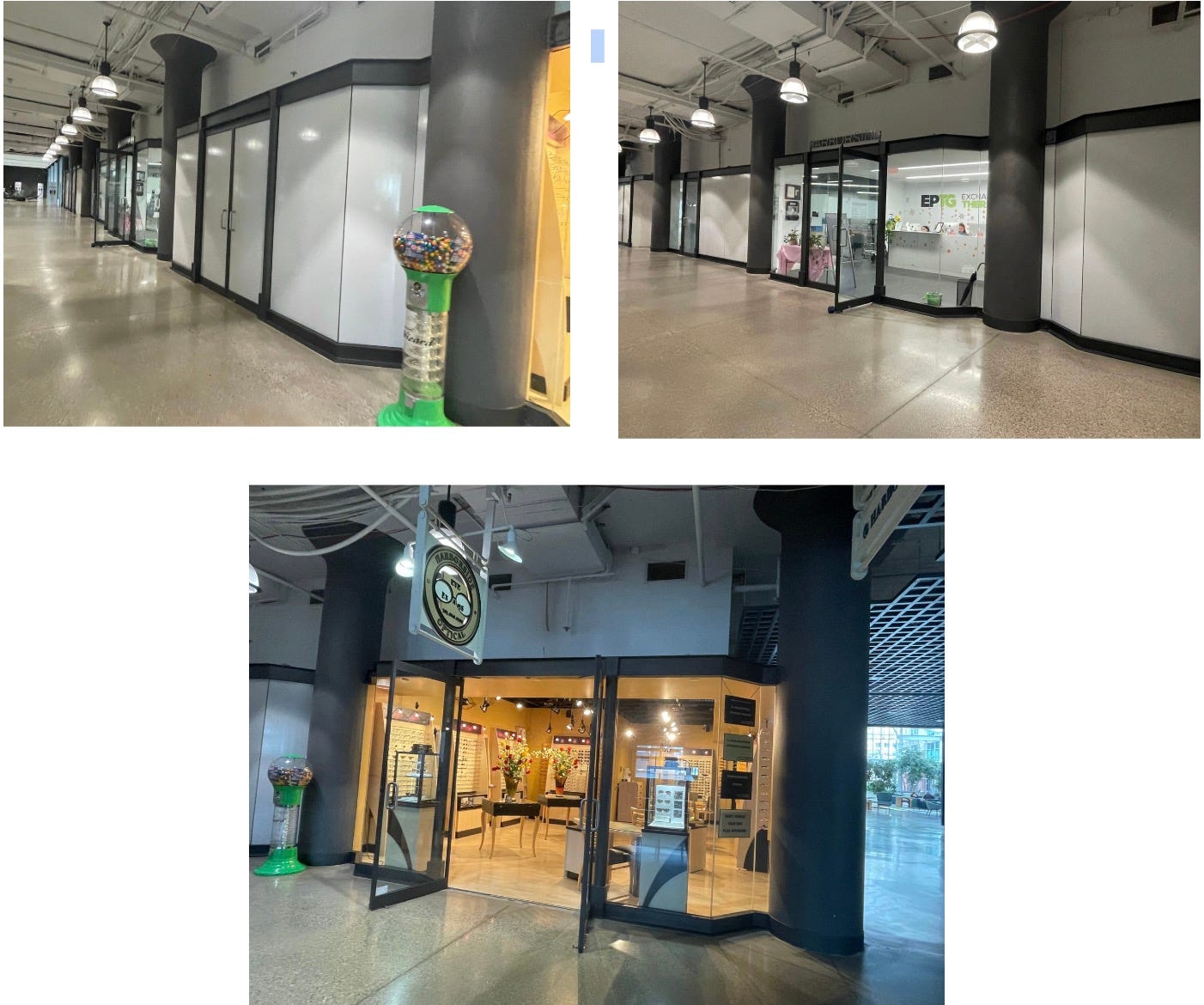

From what I’ve read online, Harborside used to be bustling, flooding each day with foot traffic from the offices housed upstairs and scattering the area nearby. When Covid hit and sent all the office workers into their individual homes, though, stores shut down due to lack of business, and now, there’s very little left. The storefronts are empty husks save for a physical therapist and a glasses store, and most people pass through without pausing.

What’s jarring to me about Harborside is that it’s gorgeous and spacious and yet consumed by this guttural emptiness, like something just on the precipice of total collapse. On Reddit, various people vent about the building’s identity crisis, its inability to shift completely beyond its past life despite having no real way of returning to it. I can’t make sense of how the building operates when most people who come through here are spending no money to use the space. I can’t make sense of how everything remains perpetually spotless when people are constantly eating in here, even bringing in pets. The bathroom is always gleaming, but the long, gaping hallway you pass through to reach it creates a sense of decay, and I find myself disoriented by what I can’t explain: why are there so many electrical outlets but none that work? Why are there two foosball tables in the back, sectioned off so no one can use them? Why is it impossible to figure out what time they even close?

Most of all, what is the point of this place? Around me, everyone is absorbed in something different. I eavesdrop on realty meetings and discussions about investments while parents pass through pushing children in strollers and people in the lounge at the corner of the atrium are busy getting drunk. Meanwhile, people file through turnstiles on the two long hallways at either edge of the room, and while I can assume they’re coming from the rooms upstairs that I can see faintly through the windows overhead, I know nothing of what goes on up there.

It took me a while to realize that, above all, Harborside is a liminal space. While it’s glossier than the dim hallways and murky stairwells that populate the Internet, where liminal spaces have been trendy in recent years, the building has all the key characteristics: it’s an area with no obvious purpose, designed not for remaining in but for drifting through.

Timothy Carson from The Liminality Project suggests that we’re mesmerized by liminal spaces because of our “desire to examine the overlooked textures of everyday life.” Without obvious context, we struggle to slot these spaces into clear categories, forcing us to look more closely at the specifics. I recognize this attentiveness when I’m in Harborside, which doesn’t match any prototype I already have for an everyday space, my attention straying towards the stock photos of flowers and trees that loop on projectors behind me, like AI-generated images of calm.

There’s also something eerily comforting about working somewhere undefined. In a 2018 study, creative professionals were asked to temporarily shift to work spaces on a rural archipelago in Finland and found that this makeshift liminal space let them reflect on their usual habits from a distance. Further, with the usual distractions stripped away, participants could tune into their actual needs and alter their daily rhythms to better suit these.

For a long time, I’ve had a habit of seeking out a certain kind of space—not only liminal but also beautiful and unoccupied—and creating ritual from it. In Virginia, where I grew up, this was a cemetery I used to run to in early evenings, slipping through a break in the fence and finding myself surrounded by a wide nothingness, green hillsides dotted in flowers and graves. I also spent afternoons pacing a rose garden in Boston’s Back Bay, watching the late-night churn of bicycle tires from a balcony in Amsterdam, and circuitously sprinting past a church in Denver. Then there was college, when I planned my running route around a startling red house that seemed to almost lurch from the monotone suburb around it.

I use these untouched spaces to exist, momentarily, outside of myself, where I can invent my own realities outside what’s already defined by other people’s presence. I return to these places by choice, with no compulsion, and map my way between tombstones and pools of gleaming blue, or spy on parties in cigarette apartments, or stare into blood red shutters, imagine that the house itself has a pulse.

Remote work always seemed like the dream to me until I actually started doing it. After graduating college, I couldn’t stand the idea of suddenly losing the independence I’d had ever since I was fifteen and started going to high school online, dictating most aspects of my schedule myself. But working from home lacks the limitedness of my teenage years, when I always had a keen awareness of my freedom being drained from me.

After weeks writing pitches in my apartment, I became restless, wondering constantly if my routine would ever evolve into something less mindless. I can’t imagine doing anything other than writing long-term, but I also can’t imagine spending too much longer being this solitary. Sitting on my bed or at the table in the living room every day gets numbing pretty fast, the private nature of my work exasperating in its repetition. I missed being in college, when my friends and I were all living in a similar rhythm, when my social life spilled into my coursework instead of staying confined to when I have time and am not too exhausted. I missed the nameless familiarity with the students who sat at adjacent tables, recurring characters in my eavesdropping.

About a month after I moved to New Jersey, I became determined to be around more people again. I wanted a place I could go where I was not just passing through, a place devoted completely to work so that I wasn’t spending half my time consciously fighting the drift of my attention in the same rooms where I sleep and eat dinner.

Harborside seemed like a miracle cure for my mounting frustration. Online, the building advertises itself as a “waterfront workplace” that’s helping to usher in the future of work. You can rent out a private office, or you can simply sit in the liminal, create something purposeful from the signifiers of work that surround you: the rattle of laptop keyboard, the placid scroll of a spreadsheet.

The term liminality actually comes from anthropology, where it refers to a state of transition between clearly defined periods in a person’s life—moments of existence where your sense of identity or social structures are stripped from you, waiting to be reinvented. In an article for The Atlantic, Jake Pitre proposes that liminal spaces are trendy because they serve as a spatial representation of these more abstract feelings of uncontrolled uncertainty. These spaces make our anxieties easier to grasp, rooting them in concrete formations that we can connect over, recognizing our directionlessness as something we share.

I’ve realized this may be what draws me to Harborside: the way it feels just as confused as I do, perfectly embodying the aimlessness I’ve felt since graduating from college last spring, the discomfort of lingering in a place where most people are simply passing through. On the phone with my mom, I tell her that the murmur of jazz bleeding through from the background is a live keyboard player, and she goes, “Live music? I thought you were in an abandoned mall!”

This moment in my life has a similar dissonance. I’m living in New Jersey so I can be near my friends while I’m figuring things out, not because I plan to stay around here long-term. I spend my days working part-time at a non-profit, pitching freelance articles: a piecemeal of projects I don’t know how to summarize when people ask what I do. Everything feels tenuous: I have no idea where I’ll end up living, or how I’ll earn money, or what my daily life will revolve around. I keep asking myself what comes next—a difficult question to answer when I don’t even know how far into the future my current era extends to.

Maybe this is what’s so striking to me about Harborside: the way I become deeply aware when I sit in here, watching people whose faces I never once recognize pass through with necks craned over their phones, that I’m currently rooted in nothing. Harborside not only makes all of my greatest fears tangible but actually forces me to sit inside of them, to look them in the eye. The hollow of the atrium isn’t just physical emptiness; it’s the same feeling that settles over me late at night when I start ruminating on whether anything I’m putting my energy into is relevant at all to my future. In both spaces, severed from any stable routine, I get this feeling that I could do anything. In Harborside, I’ve cried, slept with my head on the table, gazed pointlessly into space for hours. Meanwhile, I wake sometimes in the middle of the night and instead of going back to sleep, I make frantic voice recordings or roam the deflated streets around my apartment, or cry at four in the morning on the couch because everyone is asleep, and no one will know, and none of it will matter, and I sort of wish that it did. It almost makes me want to push myself to some kind of undefined edge, if only to feel some resistance, a limiting force I don’t have to conjure for myself.

Writing about the liminal, Michele Debczak points out that we tend to derive pleasure from experiencing our fears in low-stakes contexts, where we can lightly expose ourselves to the genuine threats we’ll face later. Within Harborside’s walls, all my decisions are short-term: which publications I’ll pitch today, how much of my afternoon I’ll devote to a current piece. Then in the evening, I step back out into my life, traipse back across the train tracks and sense this jolt of anxiety about what I will do not tonight but later on, in this shapelessness I cannot imagine becoming clear.

In middle school, I became hooked on an online quiz where you have fifteen minutes to type in the names of all the countries, and for years after, I would go through phases of playing it every day until I could recite them so easily it felt tedious. Since then, I’ve been briefly obsessed with quizzes on everything from the capitals to the flags to the sketched outline of every country.

The latest of these fixations was Geoguessr, which, if you’ve never played it before, is a game that drops you Google Earth-style into a random location somewhere in the world, leaving you to pinpoint the closest possible location on the map. The sheer possibility is addictive—I’m on a dirt path lined in shrubbery, a cramped city street with advertising splashed across the storefronts, then perched on the edge of a boat traveling under a bridge somewhere. From here, I survey the plant life, the language on the signs, sometimes running across a highway sign or a flag if I’m lucky.

I don’t entirely understand why I enjoy this so much, especially as someone who can’t even get around her hometown without a GPS, but there’s something weirdly calming about orienting myself to something distant from my actual life—like an opportunity for both familiarity and escape. It helps that these arbitrary sites aren’t landmarks, already claimed; instead they’re like glitches in space that I can dissolve into, make irrelevant meaning out of. Repeatedly, the game hurls me into the liminal, the nowhere, and for 120 seconds at a time, I put a name to what’s anonymous, I peel away the uncertainty, assign context to vague patterns of trees.

In an essay for Aeon, Suzanne Joinson divulges that, during a period of intense travel, despair would engulf her in hotel rooms, her lack of attachment to these interchangeable spaces making her feel both imprisoned and horribly adrift. It’s the endlessness of Joinson’s disorientation that makes this especially brutal—and in the same way, I’ve realized that Harborside will never fully satisfy my need for the liminal when I can’t just label it on a map and return to the certainties above my computer screen. I linger too long. I sit at these stale tables and listen to the churn of elevator music, jazz songs looping into a numbness that feels inescapable; I feel my eyes skip again over the sterile fake plants with their artificially carved leaves that pretend to bloom wildly from the pot, and everything feels sterile, impossible to continue into. The isolation of my work doesn’t go away but only becomes more pronounced as people drift past me, rarely remaining.

I tell myself I can’t establish an existence if I’m already trapped inside one. I tell myself should be grateful for this malleability: how, if I want to, I can work all night and sleep all day, can sit outside to pitch editors or take a shower in the middle of the workday or ride the train into some random part of the city for the afternoon. But I’m tired of this relentless open space. I want a routine I don’t have to assemble from nothing. I want to stop liminality from becoming a demarcated location of its own, a concrete entrapment rather than a breathing space, a possible.